Op 4 november 2016 heeft Dick van Engelen zijn oratie gehouden ter aanvaarding van de positie van Extraordinary Professor of Intellectual Property Litigation and Transaction Practice bij de Maastricht University.

Photo: Phillipe Halsman

1. EINSTEIN’S ‘INVENTIONS’

What does Einstein – Time Magazine’s "Person of the Century” – have to do with patent law? A lot, very little and something. A lot, because he came up with a large number of breakthrough inventions; impressive victories of "mind over matter”. Very little, because his great inventions were almost all of the unpatentable kind. And something, because he had his so-called "Miracle Year”in 1905, while working as a patent examiner at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern.

In his "Annus Mirabilis”, Einstein published four articles that contained inventions which changed the perspective on light, space, time, mass, and energy.

(i) The law of the photoelectric effect: light energy consisting of tiny particles (quanta or photons). For this theory he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.

(ii) The existence of molecules and atoms (as an explanation for Brownian motion – the effect that small particles suspended in a liquid jiggle around).

(iii) The mass–energy equivalence: E=mc2. The energy contained in a object equals its mass multiplied by the square of the speed of light object. Given that the speed of light is 300.000 kilometers per second, the formula implies that any small amount of matter contains a very large amount of energy

(iv) The special theory of relativity: time and space are interwoven into a single continuum known as space-time. Events that occur at the same time for one observer can occur at different times for another observer.

Patents are means to further innovation and enhance the "state of the art”. For that reason patents are published and the patent register functions as a directory disclosing an immense pool of technology. It would be convenient for the patent community, if we can claim that Einstein’s inventive insights were the direct result of his work at the Patent Office. Unfortunately, there seems no evidence that really supports such a claim.

However, the content and nature of Einstein’s inventive insights can be used to illustrate how patent law can play its part in achieving one of the objectives of intellectual property rights: the promotion of technological innovation.[1]

Einstein was a child of his time and that time was during the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution. The invention of electric light resulted in numerous patent applications on that subject, following Edison’s famous application for a light bulb in 1880. The introduction of rail road networks, for the transportation of goods and people over large distances and at relatively high speeds, meant that there was a need for the standardization of measuring distances and weights and for the synchronization of time.

As Walter Isaacson[2] assumes in his biography, Einstein’s work in a Patent Office was probably part of the mix of environmental factors that helped Einstein to develop the special theory of relativity. In those days there were numerous patent applications for new methods of coordinating clocks. Einstein also lived near the Bern clock tower and the train station, just as Europe was using electrical signals to synchronize clocks within time zones, In other words, Einstein’s insights were based upon and did enhance the state of the art and were ‘in sync’ with what the persons skilled in the art – engineers, theoretical physicists and mathematicians – were occupied with. His primary sounding board for the development of his ideas consisted of a group of colleagues and friends in Bern, informally referred to by themselves as the “Olympic Academy”. Among them was his old friend Michele Besso, who also worked at the Patent Office.

2. THE RELATIVITY OF SIMULTANEITY

In his 1916 popular explanation of his theory of special and general relativity Einstein frequently uses the setting of a moving train and two different perspectives of observation (as shown in his schematic drawing below): (i) the perspective of a person (M) standing on the railway embankment and (ii) the perspective of a person (M’) inside a train moving at a velocity (v):[3]

Einstein uses a thought experiment – two strokes of lightning striking the rails at two different places (A and B) – to demonstrate the relativity of simultaneity. Put differently: it is impossible to say in an absolute sense that two events which are separated in space occur at the same time, because time is relative to space. It is the concept he refers to as “space-time”: space and time combined into a single interwoven continuum.

In Newton’s world of physics distances, weights, time, forces, velocities and accelerations were regarded as absolute phenomena that can be measured in an absolute manner using measuring standards as meters or miles, seconds and kilograms or ounces and meters per second. Classical physics worked with the following postulates or premises:

1) Physical laws operate in the same way in different frames of reference.

2) The speed of light is absolute and not dependent on the velocity of the body emitting the light.

(c = 300.000 km/sec).

3) Time is absolute.

The concept that time is absolute – that Newton’s clock ticks at an unforgiving pace for all of us – is captured in an easy to remember way for non-physicists in the Rolling Stones song “Time waits for no one”.

Einstein’s thought experiment is that lightning strikes the rails at two places – (A) and (B) – which places are located at a large distance from one another. The flashes occur simultaneously. Can we experimentally prove the simultaneity of the two strokes of lightning? Einstein uses the thought experiment of the moving train to show that simultaneity is a relative phenomenon. I refer to the illustration of this thought experiment in the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The observer (C) standing still at the railway embankment at a position in the middle of A and B, will see that the two light rays emitted by the flashes of lightning will reach him simultaneously (at the same time). However, the observer (D), who is inside the train that moves at a velocity of 240.000 kilometers per second (4/5 the speed of light), will see that the beam of light emitted from B reaches him earlier than A. For D the lightning flash B occurred earlier than A.

This means that it cannot be true that both (i) the speed of light and (ii) time are absolute: something has to give. Einstein’s conclusion was that time is not absolute but relative to the frame of reference, in this case whether or not the observer is moving vis-à-vis the locations where the lightning strikes:

“Events which are simultaneous with reference to the embankment are not simultaneous with respect to the train, and vice versa (relativity of simultaneity).”

The gist of the theory of special relativity is captured in the song “Time is on my side” as covered by the Rolling Stones in 1964.[4] The connection between Einstein and the Rolling Stones may perhaps also lie in the famous photo of Einstein as taken by UPI photographer Arthur Sasse on Einstein’s 72nd birthday in 1951. It may also have provided inspiration for the famous Stones logo, in addition to Mick Jagger’s tongue and lips, as designed by John Pasche in 1971?

In 1915 Einstein generalized his theory of special relativity – which showed that space and time do not exist independently but form an interwoven fabric of ‘space-time’ – to also include gravity. The ‘flat’ space-time fabric of special relativity is distorted by the gravity forces of matter into a curved surface. One implication thereof was that gravity bends light. Einstein calculated that the bending of light by the gravitational field of the sun was 1.7 seconds of arc when taking into consideration the curvature of space-time.[5] That calculation by Einstein – by then a professor in Berlin – was proven to be right shortly after the end of World War I by a British expedition, which obtained photographs of the solar eclipse of May 29, 1919. It instantly made Einstein an internationally famous scientist and celebrity.[6]

3. THE PATENT LAW SYSTEM AS CONTRIBUTING FACTOR?

As already mentioned, there is no evidence that Einstein’s work as a patent examiner was critical for Einstein’s scientific breakthroughs in his Miracle Year.

Let us first of all clarify that Einstein’s intellectual skills and intelligence are not a yardstick for how high the bar is set at a Patent Office when measuring the patentability of inventions. That would have been the ultimate nightmare for any inventor who would have filed a patent application in 1905 and was confronted with Einstein as the examiner of his application. With hindsight, we pity the poor inventor who would challenge patent examiner Einstein by enthusiastically claiming “you can never imagine what I figured out”and would then be confronted with a charming “try me” as a response.

The yardstick for determining what an invention is – what is obvious or not – is not the intelligence level of a genius, but that of the hypothetical “person skilled in the art”. Not a professor or a PhD candidate, but a practitioner in the relevant field of technology, who possesses the average knowledge and ability of such a professional and is aware of the common general knowledge in in his field. That is the easy – and “average” – part of playing the “person skilled in the art” in a patent examination role play. At the same time, that poor person is presumed to know every document that has ever been published anywhere in the world, either in a trade journal, a scientific magazine or a patent application. That is the part of the “person in the art” role that requires Superman-like qualifications. It means that being assigned the role of this hypothetical “person skilled in the art” can be seen as getting the equivalent of an Oscar nomination in the relevant field of technology. In patent law that ‘field of technology’ is referred to as “the art”, as evidence of the fact that even the average engineer (or lawyer) has a (hidden) romantic streak.

The inventive step necessary for patentability does not require that this hypothetical “person skilled in the art” could not have come up with the solution, but only that this solution would not have been obvious: does not follow plainly or logically from what was known before (the “prior art”). Was it ‘within reach’ or – in Dutch – ‘voor de hand liggend’? As a result, patents do not require the work of an Einstein-like genius. Relatively small contributions to the prior art can already be patented. Olympian leaps forward – such as the theory of special relativity theory – are not necessary.

Einstein’s work as a patent examiner cannot really be considered to have been a good training ground for his scientific achievements, since his intellectual skills were way above what was required for his work as an examiner.

So can the patent community claim any credit for Einstein’s achievements? It seems that his career at the Patent Office contributed in two ways to his Miracle Year as an unknown 26 year old patent clerk.

At the Patent Office he worked in an environment were in those days numerous patent applications regarding subject matter as time synchronization were examined and evaluated on novelty, applicability and obviousness. As an examiner Einstein had to analyze such innovations and write reports. His reports were so long on detail and analysis that Einstein wrote to his friends that he was making a living "pissing ink."[7]

Second, the work was relatively simple for him and left him with enough spare time for daydreaming and his thought experiments.[8] He referred to the Patent Office as his ‘worldly monastery’. This seems a politically correct way of making it clear that his job as a patent examiner left him ‘bored beyond belief’. That turned out to be a good thing for enhancing the ‘state of the art’ of theoretical physics, but seems a poor ‘claim to fame’ for the patent system as a contributing factor to Einstein’s inventions.

4. PATENTS AS EXCEPTION TO THE RULE

Patents are granted “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” as it is famously stated in the Patent and Copyright Clause of the US Constitution. If we could claim that Einstein came up with his inventions because he could patent them – if that was the cause-and-effect relation that made him do what he did – that could be compelling evidence of the added value of the patent system. However, as Einstein knew very well, his inventions were all of the kind that is absolutely barred from patentability.

The fact that Einstein’s findings are not patentable is a telling example of the limited nature of the subject matter that can be patented. At the same time it illustrates an important justification of the patent system, being that patents do now protect knowledge ‘per se’, but only specific inventive applications thereof.

Patents, as all other intellectual property rights, are an exception to the rule that human creations are part of the public domain. Justice Brandeis of the US Supreme Court stated it elegantly in 1918 in his often quoted dissenting opinion inINS v AP:[9]

“The general rule of law is, that the noblest of human productions -- knowledge, truths ascertained, conceptions, and ideas -- become, after voluntary communication to others, free as the air to common use."

The fairness of that rule is obvious, given that human creations do not originate in a vacuum, but build upon generally available public knowledge: the cultural heritage of mankind as accrued over the ages. That public knowledge is generated, collected and transferred by, for instance, public institutions as schools, universities, libraries, and – in today’s world – Google and Wikipedia. This principle is also codified in, for instance, article 52(2) of the European Patent Convention (“EPC”) by providing that (a) discoveries, scientific theories and mathematical methods and (c) schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, shall not be regarded as patentable inventions.

Knowledge per se – the “know what” – is unpatentable and rightfully so. Patentability is limited to technology: the practical application of knowledge. Knowing how to solve a problem and to obtain a practical result is the domain of patent law.

Let us go back to Einstein’s special and general theory of relativity. These scientific theories are not patentable as such. However the practical application thereof is patentable. A practical application of Einstein’s findings on relativity can be found in GPS devices that need to compensate for the fact that atomic satellite clocks are moving at a speed of 14,000 kilometers per hour, which is much faster than clocks on the surface of the Earth. In addition they are at 20,000 km above the Earth and therefore experiencing a gravity force that is four times weaker than on the ground. Einstein's special and general relativity theory then learn that the net result of these factors is that time on a GPS satellite clock advances faster than a clock on the ground by about 38 microseconds per day. If left uncompensated for, this would cause navigational errors that accumulate faster than 10 km per day. This knowledge as such is unpatentable. However, putting this knowledge to use – knowing how to correct for these errors – is the kind of practical application of knowledge that patents may protect.

For the same reasons, Einstein’s formula E=mc2 is unpatentable as a fundamental law of nature. However, the practical application of that knowledge, that unleashes the destructive energy that is captivated in atoms – by either building an atomic bomb or a nuclear power plant – is patentable.

5. PUBLISH OR PERISH

This phrase, coined to describe the pressure in academia to continually publish academic work as a necessity for furthering one’s academic career, also holds true for inventors.

A patent grants an exclusive right for a limited time of 20 years, provided that the invention is published. That publication needs to be ‘up to the hilt’, meaning that a patent has to disclose the invention in a manner sufficiently clear and complete so that it can indeed be carried out by a person skilled in the art (article 83 EPC). The inventor gets a monopoly, provided that he or she teaches all of us what we need to know to be able to ‘infringe’ that patent. We want the inventor to make his invention publicly available so that we can all learn and build upon his contribution to the state of the art by way of improving upon it. At the same time we, as a society, promise that we will all behave like law abiding citizens and have the decency not to infringe the patent for as long as the patent exists during the maximum period of 20 years from the application date.

The alternative for patent protection is trade secret protection. Trade secret protection is usually not a viable option for inventive products, since those can usually be reverse engineered once they are out on the market. For inventive processes, however, trade secret protection may be a real alternative to patenting, if and when the actual method or recipe cannot be discovered by analyzing the product that comes out of the secret process. The archetypical example is the Coca Cola recipe, which may enjoy eternal exclusivity, provided nobody violates a contractual confidentiality obligation by divulging the secret and publishing it on a website. The societal downside of trade secret protection is that we are all kept in the dark and the public domain is not enriched with the secret knowledge.

By granting a patent and luring the inventor into publishing his new insights, we collectively learn much faster and may be able to benefit from a flywheel effect driving innovation. That will serve the public interest by improving public health and welfare at a much faster pace than without the help of published patents. The public domain – the pool of publicly accessible knowledge – is thus not only fed by publications of academic scholars but also by patented results of applied research, which disclose all kinds of technologies.

6. SCOPE OF PROTECTION

Patents draw a line between the exclusive private domain of the patentee and the public domain that others can use without infringing the patentee’s exclusive right. For this balancing act between the private property of the patentee and the public domain to work, the lines of demarcation between the these two domains needs to be clear and predictable.

If a third party cannot tell with a reasonable degree of certainty where the private property of the patentee stops and where the public domain begins, the patent system will not be able to play its part as a means for stimulating innovative initiatives by numerous third parties. In that case, patents may turn out to be stifling innovation instead of speeding it up: ambiguity about where a patent draws the line in the sand that competitors should not cross will actually function as a disincentive for innovation. Such ambiguity only stimulates maintaining the status quo – doing things as they always have been done – because changing things will simply introduce the risk of being found to infringe a patent.

Being able to determine where the line of demarcation between the exclusive domain of the patent and the public domain is to be drawn, is therefore an absolute necessity if that patent system is to function properly. Article 69(1) of the European Patent Convention (“EPC’) makes it clear that the “claims” made in a patent are the instrument that has to be used to determine where the patent draws a line in the sand, by stating the following:

The extent of the protection conferred by a European patent or a European patent application shall be determined by the claims. Nevertheless, the description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claims.

Put differently and in the words of judge Giles Rich of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit: “The name of the game is the claim”.[10] That being the case, then what is the issue? The issue is that patent claims read like poetry … but … poetry written by engineers. That combination warrants that reading a patent claim in some cases easily amounts to ‘tea-leaf-reading’.

The claim is therefore not the end of the story, as article 69 EPC also makes clear. Language is by nature an imprecise instrument to describe the boundaries between two domains. This is even more true when it comes to determining the outside borders of a patentee’s private property, given that the domain of the patented invention is by definition new and inventive and thus unknown at the time of drafting the application and the claim.[11] Therefore, interpretation of claim language will always be inevitable, as article 69 EPC also illustrates by opening the second sentence with “nevertheless”. Article 69 EPC also makes it clear that the primary tools that can be used to interpret the claims are to be found in the patent itself: the description and the drawings, which– together with the claims – constitute the three building blocks of a patent.

Lawyers are lawyers, and will always be able to find wiggle room when it comes to interpreting a particular word or definition. Therefore the EPC-legislator also codified a set of rules on how to interpret article 69 EPC. These rules are given in the Protocol on the Interpretation of Article 69 EPC.[12] Simply put, the primary rule is that article 69 EPC is to be interpreted as defining a position which combines (i) a fair protection for the patentee with (ii) a reasonable degree of legal certainty for third parties. Being fair to the patentee and giving legal certainty to third parties are the two opposing interests that need to be reconciled, when determining where exactly the exclusive and private domain of the patentee stops and the public domain, where everybody else can freely roam without infringing the patentee’s patent, begins.

7. THE SILLY WALK PATENT: A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT

Let us look at a hypothetical patent to clarify some issues. There is a famous “Ministry of Silly Walks” sketch by Monty Python.[13] Michael Palin plays the role of the developer of a silly walk and he likes to obtain a government grant to help him develop it. John Cleese is the examiner. Like Einstein, we will do a thought experiment. Our thought experiment is that we will look at the sketch as if Michael Palin is applying for a patent instead of a subsidy. This way we will get a good picture of the patent application procedure and the consequences of drafting a particular claim for an invention.

A patent claim for Michael Palin’s Silly Walk Patent could – building upon the summary as given by examiner John Cleese – be drafted as follows:

A patent is supposed to solve a problem and one may wonder what the problem, as solved by the Silly Walk Patent, is supposed to be. With the help of hindsight, it is clear that the problem that Michael Palin’s walk solves can be described as “how to walk silly in a sustainable, energy-saving way?” Using the problem-solution-approach will then learn that this method is new over the prior art, which comprises John Cleese’s silly walk[14], and is probably not obvious for the person skilled in the art of walking silly.

Now that we have written the claim of Michael Palin’s Silly Walk Patent, the question then is what kind of other typical walk may perhaps infringe this patent. For those who know their classics an obvious candidate for an allegedly infringing walk is John Cleese’s “Funny Walk” that can be seen in Fawlty Towers’ sixth episode, which is also remembered for Cleese’s famous line "Don't mention the war". John Cleese can be seen goose-stepping as part of a quiz, which is introduced with the words: “Who's this then? I'll do the funny walk.”[15]

The good news is that John Cleese’s Funny Walk is clearly outside the scope of protection of the Silly Walk patent claim. Contrary to the claim the right leg is as funny as the left leg and the ‘funniness’ of the left leg is not limited to ‘every alternate step’, to name just a few distinguishing elements.

Since we are doing a thought experiment, we can also play with the facts. Let us assume that an alleged infringer – whom we will call “B” – walks silly by doing the opposite of the claimed method. In B’s walk the left leg is not silly at all and the right leg merely does a forward aerial half-turn every alternate step. So when reading the claim on what B does, one would see:

Does B infringe? We immediately see that B is clearly not doing what the claim requires and if the language of the claim is decisive, B cannot be found to infringe. On the other hand, it seems obvious that B only came to his silly walk because he or she must have known of the Silly Walk patent claim language and simply tried to design around that claim. In this case B seems to be able to benefit from poor claim drafting by Michael Palin’s patent attorney. If the Silly Walk Patent is new and inventive, there is no reason why the same is not true for this obvious variant, which could – and should – have been claimed as well. Clearly, a missed opportunity.

Judges are judges and will – rightfully so – always feel a desire to do justice, which in this case may result in an urge to help our poor patentee. Article 69 EPC and the Interpretation Protocol also make it clear that the claim can be interpreted and that a judge therefore has wiggle room to circumvent the constraints of the claim language. An obvious way to help the patentee is by giving weight to “the inventive idea behind the words”[17] or “the meaning of the technical teaching protected in the patent claim”[18] to determine the scope of protection. Such an approach effectively means that the Silly Walk patent claim is rephrased as follows:

It is clear that if this approach is allowed to determine the scope of protection of the Silly Walk patent then B runs a serious risk of being found to infringe. That threat may cause B to change his silly walk even more to avoid such this potential infringement. Reading the claim in that light, it is clear were the wiggle room for B is, if he wishes to stay outside the scope of protection of the Silly Walk Patent and still wishes to enjoy his basic human right to walk silly without trespassing on the patentee’s private property by simply taking a silly stroll in the public domain.

So, where and how are we to draw the line between the exclusive domain of the Silly Walk Patent and the public domain that other silly walkers should be able to enjoy?

8. THE INTERPRETATION PROTOCOL

Looking at article 60 EPC[19] it is clear that out of the three building blocks that a patent is made of – the claims, the description and the drawings – the claims are decisive, while the description and drawings are only there to interpret the claims.

But what does the Interpretation Protocol[20] tell us? The generally accepted view seems to be that the Protocol only tells us to stay away from the so-called two extremes: (i) that interpretation of the claim is only warranted if the strict, literal meaning of the claim language contains an ambiguity, and (ii) that the claims serve only as a guideline and that the protection may extend to what – simply put – the patent proprietor may have contemplated. These two negative instructions do not provide guidance on what we are to do, other than staying away from these extremes, as expressly stated in the first part of the third sentence of article 1 of the Interpretation Protocol: article 69 EPC “is to be interpreted as defining a position between these extremes”.

However, all of this is only introductory language. The true instruction is in what follows in that third sentence: we are to combine (i) a fair protection for the patent proprietor with (ii) a reasonable degree of legal certainty for third parties. It seems to me that this means that any and all interpretation of (elements of) a patent claim should be tested against these two principles. Consequently, the Interpretation Protocol basically requires that two questions always need to be answered when considering a particular claim interpretation: (i) is the result fair to the patentee and (ii) does it give reasonable certainty to third parties?

However, the case law of the English, German and Dutch courts teaches us that the Interpretation Protocol is not interpreted as requiring that these two basic principles always need to be applied and tested.[21]

For England and Wales, Lord Hoffmann has learned in the Kirin Amgen-decision[22] of the House of Lords of 2004 that his own so-called Protocol- or Improver-questions[23] from the Epilady-case of 1990[24], are only guidelines for applying “the principle of purposive construction which I have said gives effect to the requirements of the Protocol”. According to Hoffmann the principle of purposive construction, as introduced in the Catnic-case,[25] is that the “question is always what the person skilled in the art would have understood the patentee to be using the language of the claim to mean.” Hoffmann may claim that this question, as the application of the principle of purpose construction, gives effect to the Protocol requirements, but (i) the question whether the protection is fair and (ii) the question whether the result accomplishes reasonable certainty, are not specifically included. It seems to me that a person skilled in the art may understand that the patentee uses certain claim language to mean that a broad scope of protection is intended, but that this is not necessarily fair to the patentee and may also be violating the principle of reasonable certainty for third parties.

For Germany, the central question set forth in the Formstein-decision of the Bundesgerichtshof of 1986,[26] seems to be whether the person skilled in the art understands that certain means are equivalent to the means that the invention uses to solve the problem. In that context the “fair protection for the patent proprietor” seems to be given priority by referring to it as an end – “das Ziel” – while referring to the “reasonable degree of legal certainty for third parties” as something that needs to be taken into consideration. This seems to imply a hierarchy between the two Protocol questions that cannot be found in the text thereof. The further elaboration of Formstein in the questions developed in the Kunststoffrohrteil-, Schneidmesser I and- II-, and Custodiol I and -II-decisions of 12 March 2002 focus on (i) the same technical effect, (ii) obviousness of that same technical effect and (iii) whether that insight is drawn from the teaching of the patent.[27] In that way the focus does not seem to be first and foremost on the two Protocol principles of (i) fairness to the patentee and (ii) reasonable certainly for third parties. In addition these questions are also different from the Improver-questions as developed by Hoffmann in the Epilady-case.[28]

For The Netherlands, the Hoge Raad gives weight to “the inventive idea behind the words of the claim” or “what is essential for the invention for which protection is invoked” as a point of view that needs to be taken into consideration. However, other possible viewpoints are also relevant, such as those that can be derived from (i) the description and the drawings of the patent, (ii) the prosecution history (but only to the benefit of the alleged infringer), (iii) the prior art and (iv) the perspective of the person skilled in the art.[29] There is no particular hierarchy for all these possible points of view and not all of them need to be taken into consideration in every individual case.[30] The Hoge Raad claims that working with these viewpoints is in conformity with the Interpretation Protocol, but given that the Protocol principles of (i) fairness to the patentee and (ii) reasonable certainly for third parties are not put at the forefront as the ultimate yardstick for weighing all these different points of view, I fail to see how this hotchpotch of viewpoints warrants that the two Protocol questions are indeed in the end decisive for the judgment to be given.

The conclusion seems to be that these national courts certainly try to apply and interpret article 69 EPC and the Interpretation Protocol in a uniform and harmonized way, but that in reality it is difficult to see that this goal is indeed achieved, if only because these courts still seem very much influenced by their own national patent law heritage and an inclination to safeguard bits and pieces of that heritage seems to prevail.[31]

It seems to me that a truly harmonized and uniform application and interpretation of article 69 EPC requires that these courts start anew by acknowledging and respecting that the Interpretation Protocol requires that (i) fairness to the patentee and (ii) reasonable certainly for third parties are the final hurdles that any claim interpretation rule needs to take. That also requires that it should always be made clear – when developing certain claim interpretation rules, sets of questions to be answered or list of viewpoints that can or need to be considered – whether and how such rules, questions and viewpoints are necessary to warrant either (i) a fair protection for the patent proprietor and/or (ii) a reasonable degree of legal certainty for third parties. Simply adhering to such a method of accountability would make it easier to make sure that when comparing national case law one does not end up comparing apples to oranges.

9. THE PRINCIPLES OF FAIRNESS AND REASONABLE CERTAINTY

Let us look at a few examples of what the principles of (i) fairness to the patentee and (ii) reasonable certainly for third parties actually mean.

Reasonable certainty for third parties[32] basically leads to Wysiwyg: “What You See Is What You Get”. It seems to me that such is at odds with giving weight to “the inventive idea behind the words of the claim” or “what is essential for the invention for which protection is invoked” as the Hoge Raad states in its case law. Since claim language reads like poetry – but unfortunately poetry written by engineers – it will not come as a surprise that claim analysis may reveal that a number of ideas may lie behind the words of the claim and the discovery thereof will depend on which person skilled in the art is doing the analyzing. The principle of reasonable certainty therefore requires that the analysis should be limited to “the inventive idea as expressed in the words of the claim” or to “what is essential for the invention as claimed”.

For most lawyers “a fair protection[33] for the patent proprietor” seems to mean that the patentee is entitled to a protection that is as broad as possible. However, it seems to me that this notion of fairness is misguided in patent law. One should not forget that the claims are basically drafted by the patentee and that the patentee has had every opportunity to claim as broad and as abstract as he can possibly imagine. The patentee chooses the terminology used in the claim and determines with these words how the claim demarcates the borderline between his private patent property and the public domain. That is a unique position. It is a privilege in law that other owners of private properties usually do not have. The flipside of this privileged position of the patentee is that it is only fair if that patentee has to live with the consequences of his choices. To paraphrase the Rolling Stones: You Can’t Get What You Want But Didn’t Claim”.

It is the fairness principle that brings with it that “disclosed but not claimed is disclaimed” has to be a rule for claim interpretation. Looking at the Silly Walk Patent, this applies to any and all prior art that is disclosed in the Silly Walk Patent’s description, including the elements of examiner John Cleese’s silly walk. Given that none of these elements is claimed as an element of the Michael Palin’s Silly Walk Patent, using an unclaimed element of John Cleese’s silly walk – in addition to or in exchange for the claimed elements – will make that such a variation on the Silly Walk patent is outside of its scope of protection.

It is also because of the fairness principle that a rule for claim interpretation has to be that “an obvious unclaimed alternative is disclaimed”. Again looking at the Silly Walk Patent this applies to the B’s variation on the patented Silly Walk referred to above, in the situation that this alternative as such was not disclosed in the description or drawings. Given that this alternative is obvious for the person skilled the art, it is only fair that the patentee that fails to claim such an obvious alternative has to live with the consequences of that drafting decision.

The fairness principle can help the patentee in those situations in which it is unfair to require that the patentee had actually claimed a particular alternative embodiment of the invention, given that this was unknown at the time. Looking at the Silly Walk Patent this would apply to the – hypothetical (!) – situation in which the state of the art at the application date would be that right legs were physically unfit to do anything silly and silliness was the privilege of left legs only.

10. THEORY VERSUS PRACTICE

Article 69 EPC and the Interpretation Protocol provide for one unified set of rules for determining the scope of protection of what article 2(1) of the European Patent Convention proclaims to be a European patent. That term requires some clarification.

The European Patent Convention primarily makes it possible to file one European patent application that is examined by one patent examining authority: the European Patent Office. The added value thereof is that this single European application makes it possible to obtain a patent in all 38 member states of the European Patent Convention in an efficient and cost effective manner, instead of having to file 38 national applications with the possibility of different outcomes of these 38 national patent granting procedures. The single European application leads to one uniform European patent claim as opposed to a ‘mixed bag’ of 38 nationally tweaked and twisted – or even refused – patents.

A complication of the present system is, however, that once granted, this European patent “shall, in each of the Contracting States for which it is granted, have the effect of and be subject to the same conditions as a national patent granted by that State, unless this Convention provides otherwise”, as article 2(2) EPC states. This phenomenon is often described by saying that upon grant a European paten application falls apart into a bundle of national patents that live their own separate lives in each of the designated states. However, this metaphor is somewhat misleading and requires further clarification.

The basis for that clarification is to be found in the closing part of section 2 of article 2(2) EPC: “unless this Convention provides otherwise”. Given that the European Patent Convention provides (i) what is patentable subject matter, (ii) what the requirements for patentability (novelty, inventive step, industrial applicability and enabling disclosure) are and (iii) what the scope of protection of a European patent is, this formal bundle of national patent rights does indeed materialize as a true European Patent if it comes to determining (i) whether the patent is valid and (ii) which products or processes do infringe that patent. Those two issues are at the heart of almost all patent disputes. The two other remaining issues that are in effect subject tot the bundle of national laws are (i) the actual existence of a European patent in a particular jurisdiction (which is subject to fulfilling national continuation requirements) and (ii) property issues.

The result of the above is that both (i) the validity of a European patent and (ii) the infringement thereof are solely governed by and subject to the provisions of the European Patent Convention.[34] The outcome of any patent dispute in any of the 38 member states[35] of the European Patent Convention should therefore be the same in each of the designated states for which that European patent has been granted. In theory, the outcome of any multi-jurisdictional European patent dispute should thus be the same in all countries concerned. In practice, a uniform and level playing field, as the desired outcome of such a cross-border patent dispute, is still something to hope for but certainly not a sure thing, given that a multi-jurisdictional patent infringement dispute can be litigated in all 38 member states of the European Patent Convention.

The major stumbling block that the European patent system has to deal with is that we seem to lack a highest European court that has supremacy over the various supreme courts of the member states. Such a ‘Supreme European Patent Court’ is necessary to make sure that article 69 EPC and the Interpretation Protocol are indeed actually and uniformly interpreted and applied by the national courts. Without such a highest instance a harmonized and uniform application of article 69 EPC in multi-jurisdictional patent disputes in a number of member states is and will remain an illusion.

11. THE LEGAL VERSION OF QUANTUM MECHANICS

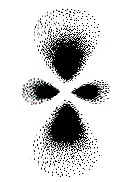

The present situation in which the highest court of each member state of the European patent Convention has the final say in how article 69 EPC and its Interpretation Protocol need to be interpreted and applied means that the outcome of any multi-jurisdictional patent infringement dispute can – and in a number of cases actually does – differ from country to country.[37] Since the European patent system lacks a safeguard for a uniform application of the uniform European Patent Convention rules on scope of protection, the present situation resembles what one might call the legal version of quantum mechanics.

In classical physics electrons are assumed to be circling around the nucleus of an atom and their location and direction is supposed to be determined by classic mechanical laws. Max Planck is seen as an originator of quantum theory, which revolutionized our understanding of atomic and subatomic processes. Simply put, quantum mechanics does away with the concept of the location and direction of electrons being subject to deterministic classic mechanical laws, but assumes that their location is instead a matter of chance with discrete different levels of probability as to where they can be.

Classical Physics Quantum Mechanic[37]

Einstein resisted quantum mechanics. Einstein’s famous catchphrase was “God does not play dice.” For a simple lawyer like me, the easy way to remember Einstein’s rebellion to quantum mechanics, as well as the gist of quantum mechanics itself, is the following photograph[38] of Bruce Springsteen performing "Tumbling Dice" with the Rolling Stones on 15 December 2012 at Newark’s Prudential Center. You see Mick Jagger and Keith Richards on stage as well as on the screen behind it, thus personifying the different non-interconnected regions where you may find an electron moving around a nucleus according to quantum mechanics.[39]

From 1925 Einstein spent the next three decades stubbornly criticizing what he regarded as the incompleteness of quantum mechanics while attempting – in vain – to subsume it into a unified field theory, as Isaacson describes.[40]

12. THE UNIFIED PATENT COURT

The good news for patent law is that, while Einstein failed, we seem to be on the threshold of getting rid of the legal version of quantum mechanics for European patent law.

On 19 February 2013 twenty-five EU member states[42] signed the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court.[43] This Agreement provides for the creation of a single, supra-national court that will – simply put – have competence to hear infringement and revocation cases in respect of European patents (including so-called unitary patents[44]). Once this Unified Patent Court will be in operation a uniform application of the European Patent Convention in infringement cases will be warranted in those member states of the European Union that will participate, because there will be one supranational court deciding infringement cases instead of numerous national courts.

However, before the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court can enter into force, it needs to be ratified by at least thirteen EU member states, including France, Germany and the United Kingdom, as the three states with the most European patents in effect in 2012.

13. BREXIT BLUES

It will be obvious that with the outcome of the Brexit referendum of 23 June 2016, the ratification of Unified Patent Court Agreement by either the United Kingdom or by any of the other states that have not yet ratified, including Germany, has become unlikely. It seems politically naïve to assume that any such ratification will take place, while the UK’s EU membership is in the balance. In addition, any continuation of a UK participation in the Agreement seems legally ‘challenging’, given that the UPC Agreement (i) is only open to EU member states and (ii) grants primacy to European Union law. The Unified Patent Court must respect and apply Union law, in collaboration with the Court of Justice of the European Union as a guardian of that European Union law.[45] As a practical matter, it seems to me that the Unified Patent Court is not likely to materialize in the coming years, in spite of the unwavering optimism that certain patent enthusiasts and the Preparatory Committee still display.[46]

The dramatic impact of this standstill of the UPC project should not be underestimated. This is the fourth[47] attempt to establish a single pan European patent court to warrant a unified scope of protection for European patents and to make enforcing a European patent in Europe more efficient and cost effective. If the Brexit materializes, it remains to be seen whether such will quickly lead to the ratification of the UPC Agreement, also given that certain countries may take the opportunity to renegotiate certain aspects that may – rightfully or not – be perceived as UK dominated compromises. To quote the Rolling Stones once more: “This could be the last time.”

But even in these dark days for the European patent community, we can still take inspiration from the sense of humour that our British friends do have in abundance. So in what later may turn out to have been European patent law’s darkest hour, I personally take inspiration from Monty Python’s “Life of Brian” and paraphrase Eric Idle’s famous opening line to Graham Chapman as Brian (while hanging on the cross): “Cheer up, patent lawyer” followed by a life lesson that all lawyers should take to heart “… always look on the bright side of the law”. That is especially true if they do not like what is coming their way and may actually turn out to be good for them, thinking of all the efforts the European patent community undertook to minimize the role that the Court of Justice of the European Union might be able to play when it comes to harmonizing and further developing European patent law.

14. THE EU COURT OF JUSTICE TAKES CENTRE STAGE

While all of us patent lawyers were busy among ourselves, the world of European law kept on turning. One of these turns dramatically affected the role that the TRIPs Agreement plays in European Union law.

The TRIPS Agreement – the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights – is Annex 1C of the World Trade Agreement, signed in Marrakesh, Morocco, on 15 April 1994. TRIPs encompasses 164 countries and therefore has an almost worldwide reach.

Both (a) the European Union as well as (b) all of its member states, are signatories to the WTO Agreement and TRIPs. Therefore, according to settled case-law, the provisions of TRIPs form an integral part of the legal order of the European Union and within the framework of that legal order the Court of Justice of the European Union has jurisdiction to give preliminary rulings concerning the interpretation of TRIPs, as the Court reconfirmed in its Merck-judgement of 11 September 2007.[48]

In its Merck-judgment of 2007 the European Court of Justice, sitting in a Grand Chamber of 13 Judges, reconfirmed – in line with its Dior-decision[49] of 2000 – that the Court has jurisdiction to interpret the provisions of the TRIPs Agreement, but when the field is one in which the European Union has not yet legislated, that field falls within the competence of the member states and consequently “the protection of intellectual property rights and measures taken for that purpose by the judicial authorities do not fall within the scope of Community law”. The Court then found that at that time “in the particular sphere into which into which article 33 of the TRIPs Agreement falls, that is to say, that of patents” there was not any Community legislation dealing with the subject matter of article 33 TRIPs, which is the duration of patent protection. Therefore, the Court ruled in reply to a reference from the Supremo Tribunal de Justiça of Portugal, that the member states remained principally competent and could choose whether or not to give direct effect to that provision of TRIPs.

This finding of the European Court of Justice in 2007 was under the regime of the Maastricht Treaty of 1992. However, the Treaty of Lisbon, which amends the treaty of Maastricht, was signed on 13 December 2007 and entered into force on 1 December 2009 and with that article 207(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”). That article mentions “the commercial aspects of intellectual property” as one of areas that is part of the “common commercial policy” of the Union and is to be “based on uniform principles”. Article 3(1)(e) TFEU also makes it clear that the common commercial policy “falls within the exclusive competence of the European Union”. Consequently the member states are no longer competent to deal with regard to that subject matter.

The impact of this change – that the Lisbon Treaty brought with regard to competency for intellectual property rights in general and patents in particular – has been addressed by the Court of Justice in its Daiichi-judgment of 2013.[50] Strangely enough, this decision of the Court, again sitting in a Grand Chamber, has not gotten much attention in European intellectual property circles and seems somewhat of a wallflower. The Court observed that the TRIPs Agreement, as an integral part of the WTO system, deals with the trade related aspects of intellectual property rights, as its very title makes clear. The Court also noted that the primary objective of the TRIPs Agreement is to strengthen and harmonise the protection of intellectual property on a worldwide scale and that TRIPs has the objective of reducing distortions of international trade by ensuring, in the territory of each member of the WTO, the effective and adequate protection of intellectual property rights. The rules in the TRIPs Agreement concerning the availability, scope and use of intellectual property rights in the TRIPs Agreement are thus intended to standardise those subjects at world level and thereby to facilitate international trade. The consequence thereof is that these TRIPs provisions fall within the field of the common commercial policy and therefore fall within the exclusive competence of European Union law, irrespective of whether or not the European Union has already legislated on that subject or not. The Merck-judgement therefore no longer represents valid European Union law and all aspects of intellectual property rights that are covered by TRIPs are now part of European Union law.

In Daiichi, the Court made that clear by ruling on the interpretation of article 27 of TRIPs that – simply put – the invention of a pharmaceutical product, such as the active chemical compound of a medicinal product, is capable of being the subject-matter of a patent. The Court then indicated (under 59) that this approach applies to “the rules concerning the availability, scope and use of intellectual property rights in the TRIPs Agreement”, as those rules are intended to standardize certain rules on that subject at world level and thereby facilitate international trade. Consequently, this approach also applies to article 28 TRIPs that provides that a “patent shall confer on its owner the following exclusive rights: (a) where the subject matter of a patent is a product, to prevent third parties […] from the acts of: making […] that product; (b) where the subject matter of a patent is a process, to prevent third parties […] from the act of using the process […].”[51]

In view of the above, it seems to me that the consequence of the Daiichi-decision is that also the scope of protection of a patent – what is the patented product or process[52] – is now part of European Union law and the Court of Justice of the European Union is now the highest authority within the European Union if it comes to interpreting that subject both with regard to European patents as well as national patents. Consequently, if it comes to determining how exactly the scope of protection of either a European patent or a national patent is to be determined – either under article 69 EPC and its Interpretation Protocol or under the corresponding provisions of national patent law – the highest Courts in the member states should refer questions to the European Court of Justice of the EU for preliminary rulings.

Although it will probably come as a surprise – if not to say ‘an unpleasant surprise’ – to most patent professionals that the Court of Justice of the EU all of a sudden may have emerged as the equivalent of a ‘Supreme European Patent Court’, I must admit that I very much welcome this development. Among IP lawyers, at least in The Netherlands, it seems to be fashionable to moan about the manner in which the European Court has gone about harmonizing trademark or copyright law. However, if one simply accepts that harmonization is not the equivalent of trying to safeguard as many old national ‘specialties’ as possible, but the equivalent of starting anew and with a clean slate in an honest effort to find as much common ground as possible, I am of the opinion that the European Court has done a good job of harmonizing European copyright and trademark law.

So for me Daiichi[53] stands for getting a view of the Promised Land and to all my grumpy patent colleagues that do not like this at all, I say – borrowing from Bruce Springsteen in his classic “The Promised Land” – you got to have “the faith to stand its ground.”

15. CLOSING REMARKS

This brings us to the end of this journey “From Einstein’s Relativity to a Unified Patent Law”. I hope you have enjoyed the ride, while on the way over we also have been bridging some gaps between Science, Patents and Rock & Roll.

A few words of thanks are in place.

To the Executive Board of Maastricht University for the confidence placed in me.

To Jan Brinkhof: I still cherish the years we jointly taught classes in Utrecht. To paraphrase Lord Hoffmann in Biogen v Medeva of 1996: for me you were the expert who ‘switched on the light’ in the dark spheres of patent law.

To my colleagues at Boek9 – the IP website – and to my colleagues at Ventoux Advocaten. A special word of thanks to my partner Susan Kaak with whom I founded Ventoux Advocaten 12 year ago: the fact that you do not take me (too) seriously makes for a powerful combination.

To the IPKM team here at Maastricht University: Anselm Kamperman Sanders, Cees Mulder, Anke Moerland, Ana Ramalho and Meir Pugatch: You made me feel welcome and appreciated right from the start. I love the ambitious spirit of Maastricht and the fact that education and teaching is seen as a core competence of a University. Combined with an international outlook, it makes Maastricht an ideal place for me. Anselm, you can be very proud of what you have established here. You started with nothing and have established a great teaching program with the Intellectual Property and Knowledge Management master and an international PhD stable that has an impressive output.

To the IPKM students: Teaching students who come from all over the world is a privilege. I am always impressed and humbled by the fact that you travel from afar and follow the IPKM-program here in Maastricht as an investment in your future. My colleagues and I hope that we can make a lasting impact that will help you in your future careers. I worked abroad twice and that certainly had a lasting impact on my professional and personal development.

To my sons Guus and Bob: I always claim that I do not put any pressure on you and that you could and should become whatever your heart tells you. That is still true and both your mother and I are very proud of who you are and what you have become. But, having said that ….. you guys are 23 and 25 by now and Einstein had his Miracle Year at the age of 26. So your mother and I look forward to being happily surprised. But like I said: no pressure.

To my spouse Annette: We recently learned that there is a coaching technique called ‘provocative coaching’ and our conclusion is that you are very good at it. At the end of my inauguration at Utrecht University in 2007, I mentioned that you have vigorously coached my scholarly writings with two iron questions: (i) do you think anybody will read this and (ii) what does it pay? You were surprised by that short summary of your support for my endeavors and by the fact that all your friends recognized you. However, that description of your contribution was a bit short, so today I conclude by referring to the song “Forever” by ‘Miami’ Steve van Zandt and The Disciples of Soul:

I gave you my heart and you loved me forever.

You picked up the pieces when I stumbled and fell.

There have been a lot of pieces to pick up.

Ik heb gezegd.

* * * * *

[1] Article 7 of the international agreement on Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPs”): “Contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and to the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare, and to a balance of rights and obligations.”

[2] Walter Isaacson, Einstein: his Life and Universe, Deckle Edge, 2007

[3] Einstein A. (1916), Relativity: The Special and General Theory (Translation 1920), New York: H. Holt and Company, section Nine: The Relativity of Simultaneity.

[4] Written by Jerry Ragovoy (under the pseudonym of Norman Meade).

[5] Einstein (1916), Relativity: The Special and General Theory (Translation 1920), New York: H. Holt and Company, Section Twenty-Two: A Few Inferences from the General Principle of Relativity and Appendix Three: The Experimental Confirmation of the General Theory of Relativity.

[6] Walter Isaacson, Einstein: his Life and Universe, Deckle Edge, 2007, Chapter Twelve.

[7] Michio Kaku, Einstein’s cosmos, 2015, Weidenfeld &Amp

[8] Walter Isaacson, Einstein: his Life and Universe, Deckle Edge, 2007: Chapter Seven: “I was sitting in a chair in the patent office at Bern when all of a sudden a thought occurred to me,” he recalled. “If a person falls, freely, he will not feel his own weight.” That realization, which “startled” him, launched him on an arduous eight-year effort to generalize his special theory of relativity and “impelled me toward a theory of gravitation.” Later he would grandly call it “the happiest thought in my life.”

[9] International News Service v. Associated Press, 248 U.S. 215 (1918).

[10] Giles S. Rich, The Extent of the Protection and Interpretation of Claims--American Perspectives, 21 Int'l Rev. Indus. Prop. & Copyright L., 497, 499 (1990); See also: Van Engelen, NJ 2013, nr. 68, case note on AGA v Occlutech, Dutch Supreme Court, 25 May 2013.

[11] See Lord Hofmann, House of Lords, 21 October 204, Kirin Amgen v Hoechst, [2004] UKHL 46, [2005] RPC 9, [82], (IPPT20041012) under 34: “[…] it must be recognised that the patentee is trying to describe something which, at any rate in his opinion, is new; which has not existed before and of which there may be no generally accepted definition.”

[12] Article 1. General principles: Article 69 should not be interpreted as meaning that the extent of the protection conferred by a European patent is to be understood as that defined by the strict, literal meaning of the wording used in the claims, the description and drawings being employed only for the purpose of resolving an ambiguity found in the claims. Nor should it be taken to mean that the claims serve only as a guideline and that the actual protection conferred may extend to what, from a consideration of the description and drawings by a person skilled in the art, the patent proprietor has contemplated. On the contrary, it is to be interpreted as defining a position between these extremes which combines a fair protection for the patent proprietor with a reasonable degree of legal certainty for third parties.

Article 2 – Equivalents: For the purpose of determining the extent of protection conferred by a European patent, due account shall be taken of any element which is equivalent to an element specified in the claims.

[13] The sketch is part episode 1, season 2 of Monty Python's Flying Circus, 1970.

[14] http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/SillyWalk.

[15] Part of the sixth episode of the BBC television sitcom “Fawlty Towers”, 1975.

[16] For the sake of full disclosure, it should be mentioned that at the occasion of the performance of the sketch as part of the “Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl” show in 1982, this version was done by Michael Palin.

[17] The “de achter de woorden van de conclusies liggende uitvindingsgedachte” in the terminology of the Dutch Hoge Raad. See: Hoge Raad, 13 January 1995, Ciba Geigy v Oté Optics (IEPT19950113); Hoge Raad, 7 September 2007, Lely v Delaval (IEPT20070907); Hoge Raad, 25 may 2012, AGA v Occlutech (IEPT20120525); Hoge Raad, 5 Februari 2016, Bayer v Sandoz (IEPT20160205).

[18] The ”Sinngehalt der im Patentanspruch unter Schutz gestellten technische Lehre“ in the terminology of the German Bundesgerichtshof in: BGH 12 maart 2002, GRUR 2002, 511, 512 (Kunststoffrohrteil); GRUR 2002, 515, 517 (Schneidmesser I) (IPPT20020312); GRUR 2002, 519, 521 (Schneidmesser II); GRUR 2002, 523, 524 (Custodiol I); GRUR 2002, 527, 529 (Custodiol II).

[19] Article 69 EPC: “The extent of the protection conferred by a European patent or a European patent application shall be determined by the claims. Nevertheless, the description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claims.”

[20] See footnote 11.

[21] For an overview I refer to the well-argued and detailed opinion of attorney-general Van Peursem of 30 October 0215 in Bayer v Sandoz as decided by the Dutch Hoge Raad on 5 February 2016.

[22] Kirin-Amgen Inc v. Hoechst Marion Roussel Limited, [2004] UKHL 46, [2005] RPC 9, under 52.

[23] The questions are: “(1) Does the variant have a material effect upon the way the invention works? If yes, the variant is outside the claim. If no?

(2) Would this (ie that the variant had no material effect) have been obvious at the date of publication52 of the patent to a reader skilled in the art? If no, the variant is outside the claim. If yes?

(3) Would the reader skilled in the art nevertheless have understood from the language of the claim that the patentee intended that strict compliance with the primary meaning was an essential requirement of the invention? If yes, the variant is outside the claim.”

[24] Improver Corporation v Remington Consumer Products Ltd [1990] FSR 181, 189.

[25] Catnic Components Ltd v Hill & Smith Ltd [1982] RPC 183, 243:

[26] BGH 29 April 1986, GRUR 1986, 803 (Formstein) under 35: “Zu fragen ist, ob der Fachmann aufgrund der in den Ansprüchen unter Schutz gestellten Erfindung dazu gelangt, das durch die Erfindung gelöste Problem mit gleichwirkenden Mitteln zu lösen, d. h. den angestrebten Erfolg auch mit anderen Mitteln, die zu diesem Erfolg führen, zu erreichen. Lösungsmittel, die der Durchschnittsfachmann aufgrund von Überlegungen, die sich an der in den Patentansprüchen umschriebenen Erfindung orientieren, mit Hilfe seiner Fachkenntnisse als gleichwirkend auffinden kann, sind regelmäßig in den Schutzbereich des Patents einbezogen. Das gebietet das Ziel der angemessenen Belohnung des Erfinders unter Beachtung des Gesichtspunkts der Rechtssicherheit.”

[27] See: Peter Meier-Beck, Scope of Protection – Protection of Equivalents? in On the Brink of European Patent Law, Eleven International Publishing, 2011, p. 29-35, Jan Brinkhof, Extent of Protection: Are the National Differences Eliminated? in“„...und sie bewegt sich doch!“ – Patent Law on the Move”, Festschrift für Gert Kolle und Dieter Stauder, 2005; Van Peursem, o.c. ;

[28] See footnote 22.

[29] See: Van Peursem, o.c., under 2.33; Hoge Raad, 13 January 1995, Ciba Geigy v Oté Optics (IEPT19950113); Hoge Raad, 7 September 2007, Lely v Delaval (IEPT20070907); Hoge Raad, 25 may 2012, AGA v Occlutech (IEPT20120525); Hoge Raad, 5 February 2016, Bayer v Sandoz (IEPT20160205).

[30] Hoge Raad, 25 may 2012, AGA v Occlutech (IEPT20120525).

[31] See also: Toon Huydecoper, Fair Protection, Liber Americorum Willem Hoyng, 2013, p. 46-64; Dieter Stauder, Developing a Uniform Application of European Patent Law in On the Brink of European Patent Law, 2011, p. 111-121; Robin Jacob, Is a New Approach by National (Supreme) Courts Required, in: On the Brink of European Patent Law, 2011, p. 121-127;Jan Brinkhof, The European Challenge, in On the Brink of European Patent Law, 2011, p. 127-150. Singer/Stauder, The European Patent Convention, Third Edition, Volume 1, 2003, Article 69, section 4 through 7.

[32] The French and German texts speak of “un degré raisonnable de sécurité juridique aux tiers” and “ausreichender Rechtssicherheit für Dritte”, respectively.

[33] In the French and German texts speak of “une protection équitable au titulaire du brevet” and “einen angemessenen Schutz für den Patentinhaber”, respectively.

[34] Enlarged Board of Appeal, 11 December 1989 (G 2/88), Mobil Oil: 3.3 […]. In this connection, Article 69 EPC and its Protocol are to be applied, both in proceedings before the EPO and in proceedings within the Contracting States, whenever it is necessary to determine the protection which is conferred.”

[35] Free clipart: Phillip Martin: http://government.phillipmartin.info.

[36] The Epilady-case between Improver and Remington is a classic example of the differing outcomes - and also differing arguments to come to a similar result – of the same patent infringement being judged by different national courts. Remington was found not to infringe Improver’s Epilady-patent with a in the UK in the famous judgement by (at the time) Justice Hofmann of 1990, in which he introduced the so-called Improver- or Protocol-questions ([1990] FSR 181, 189). The same result was obtained in Austria (OLG Wien, 31 July 1989, GRUR Int. 1992, p. 53). At the same time Remington was held to infringe in (i) The Netherlands (Hof Den Haag, 20 February 1992, IEPT19920220), (ii) Germany (OLG Dusseldorf, (21 November 1991, GRUR Int. 1993, p. 242), (iii) Switzerland (Handelsgericht Zurich, 20 June 1990, GRUR Int. 1992, p. 66), (iv) Belgium (Hof van Beroep Antwerpen, 25 juni 1990, GRUR Int. 1992, p. 66) and (v) Italy (tribunal Milan, 4 May 1992, GRUR Int. 1993, p. 249.

[37] A density plot of a hydrogen atomic orbital, in which the density of the dots represents the probability of finding the electron in that region. From Donald A. McQuarrie, Quantum Chemistry, University Science Books, 1983.

[38] Billboards.com, Ray Waddell, 16 December 2012.

[39] In the meantime, Bruce Springsteen is having the time of his live, being on stage with his teenage hero’s. See: Springsteen, Born to Run, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2016, Chapter 76.

[40] Walter Isaacson, o.c., Chapter One, The Light Beam Rider, 2007.

[41] http://e-ducation.datapeak.net/physics.htm.

[42] All member states of the European Union, except Spain, Poland and Croatia

[43] Official Journal of the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union. 56: 2013/C175. 20 June 2013.

[44] See: (i) Regulation (EU) no 1257/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2012 implementing enhanced cooperation in the area of the creation of unitary patent protection (Official Journal L 361/1, 31/12/2012) and (ii) Council Regulation (EU) No 1260/2012 of 17 December 2012 implementing enhanced cooperation in the area of the creation of unitary patent protection with regard to the applicable translation arrangements (Official Journal L 361/89, 31/12/2012).

[45] See Chapter IV of the UPC Agreement. Article 20: “The Court shall apply Union law in its entirety and shall respect its primacy.” Article 21:”As a court common to the Contracting Member States and as part of their judicial system, the Court shall cooperate with the Court of Justice of the European Union to ensure the correct application and uniform interpretation of Union law, as any national court, in accordance with Article 267 TFEU in particular. Decisions of the Court of Justice of the European Union shall be binding on the Court.”

[46] https://www.unified-patent-court.org

[47] After three failed attempts with (i) the Community Patent Convention of 1975 (Official Journal L17/1, 26/1/76), (ii) the Agreement Relating to Community Patents of 1989 (Official Journal L 401, 30/12/1989) and (iii) the Proposal for a Council Regulation on the Community Patent of 2000 (Official journal C 337 E /278, 28/11/2000). See also: Jan M. Smits & William A. Bull, The Europeanization of Patent Law: Towards a Competitive Model, in: Ansgar Ohly & Justine Pila (eds.), The Europeanization of Intellectual Property Law: Towards a European Legal Methodology, Oxford [OUP] 2013, pp. 39-55.

[48] 11 September 2007, Case C-431/05 (IPPT20070911).

[49] 14 December 2000, joined Cases C-300/98 and C-392/98, Dior and Others [2000] ECR I-11307) (IPPT20001214)

[50] 18 July 2013, Daiichi Sankyo and Sanofi Aventis v DEMO, ECLI:EU:C:2013:520 (IPPT20130718).

[51] Emphasis added.

[52] This is in line with the approach taken by the Court with regard to copyright in its Infopaq-decision of 16 July 2009 (Case C-5/08; ECLI:EU:C:2009:465; IPPT20090716). There the Court found that it followed from the fact that Directive 2001/29 provides in article 2(a) that authors have the exclusive right to authorise or prohibit reproduction, in whole or in part, of their “works”, that it is part of the jurisdiction of the Court to interpret what may constitute a copyrightable work. In the Painer-decision of 1 December 2011 (Case C‑145/10; ECLI:EU:C:2011:798; IPPT20111201) this resulted in the following test for copyrightability: as meaning that a portrait photograph can, under that provision, be protected by copyright if, which led to the following test for copyright protection of a work (under 99): “an intellectual creation of the author reflecting his personality and expressing his free and creative choices in the production of it”.

[53] On Daiichi, see also: I. van Damme, De impact van het Verdrag van Lissabon op de bevoegdheid van de Unie met betrekking tot de TRIPS-Overeenkomst, SEW 2014/120, p. 335-343; J. Larik, 'No mixed feelings: The post-Lisbon Common Commercial Policy in Daiichi Sankyo and Commission v. Council (Conditional Access Convention)’, Common Market Law Review 2015(52), issue. 3, pp. 779–799; M. Minn, ‘Patenting in Europe: The Jurisdiction of the CJEU over European Patent Law’, Perspectives on Federalism 2015(7), issue 2: 1-28.